May 11th, 2012

François Truffaut had been ambivalent about Jacques Tati’s work (he’d called the director “laborious” in correspondence with Helen Scott), prior to watching Play time (1967). Having done so, he was awestruck, and immediately wrote Tati an exquisite letter to offer him sympathy for the disappointing reception, and tell him how much he had admired a film he realised was being woefully misunderstood and under-appreciated. It moved Tati deeply: such praise would have been touching at any time, but in 1968, to have Truffaut rally to one’s support was especially significant.

The appraisal of “a film from another planet, where they make films differently” was spot on. Play time is indeed one of that handful of films of which it may be truly said that you have never seen anything similar. And unlike many others in that handful – say, for example, Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964) – it achieves uniqueness without compromising accessibility or entertainment value. It is one of the most original films ever; it might also be one of the most generous.

Why?

Tags: architecture, cinema, Claude Jade, Confusion (Tati project), Fogo e Paixão, François Truffaut, Ingmar Bergman, Isay Weinfeld, Jacques Tati, Jean-Claude Carrière, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Jorge Luis Borges, Jour de Fête, L'École des Facteurs (short), Les vacances de M. Hulot, Márcio Kogan, Mon Oncle, Parade (film), Peter Greenaway, Play Time, Sparks, The garden of forking paths, Trafic

Posted in architecture, cinema, music, the way we live now | Comments Off on Tativille 2: “Ce ne sera plus mon film”

(it will be my film no longer)

January 11th, 2011

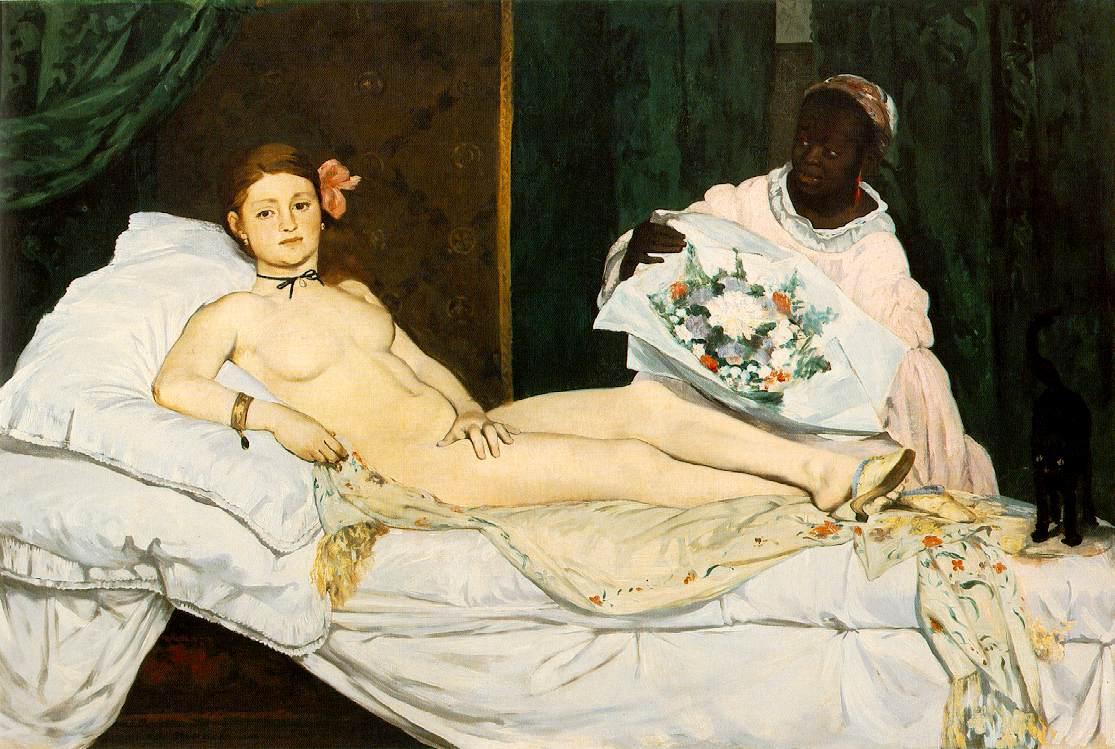

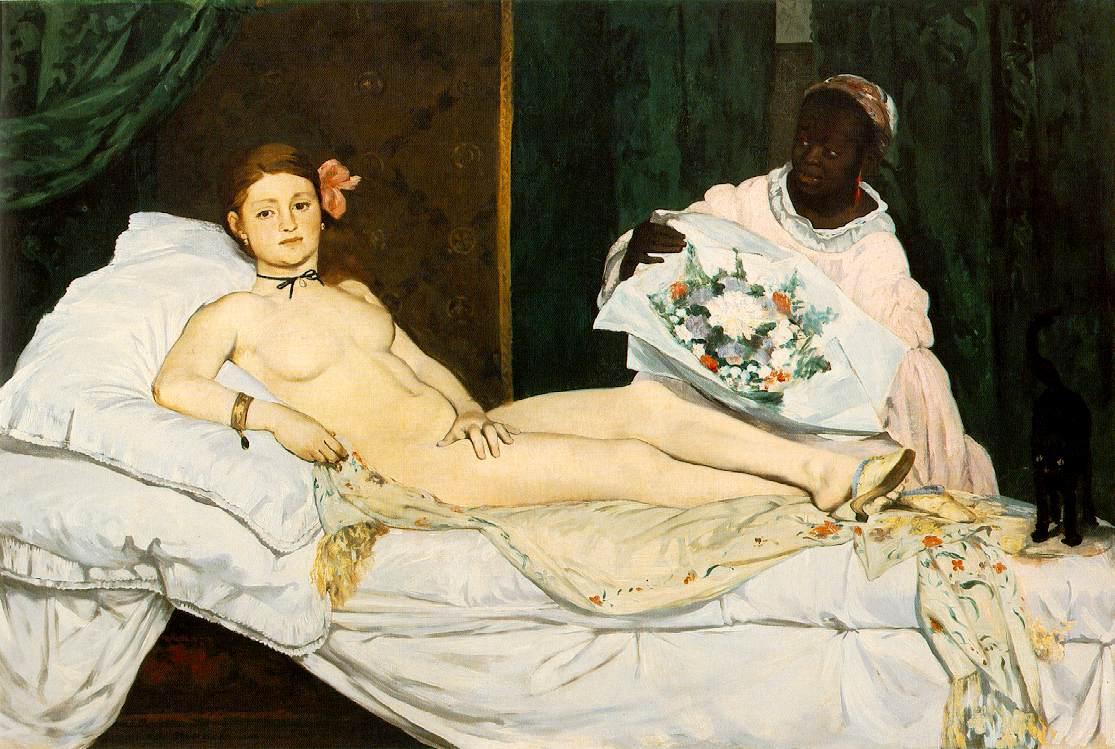

Édouard Manet, "Olympia" (oil on canvas, 1863), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Much of Olympia (2011) came from the sessions of what would have been Roxy Music’s reunion album – a full reunion, including Brian Eno – announced as such some five years earlier, and as such, generating a fair amount of trepidation. Eventually, Bryan Ferry decided the reunion wasn’t such a good idea after all, and the material was remodelled.

It was the right decision. Echoes of Roxy notwithstanding, Olympia was very much his album, and none the worse for that. Getting Ferry, Eno, Manzanera and McKay back together in the lab still produces something pretty special, but the reaction that gave us Virginia Plain (1972) would have been impossible to recreate: after 40 years of changes to its elements, it would be insane to expect the formula to yield the same results. That is fine: Virginia Plain is still here, as are Roxy Music (also 1972), Pyjamarama and For Your Pleasure (both 1973), regularly remastered and reissued, readily available. They need no re-making or re-modelling; in fact, it would have been offensive for Roxy to get back together and rehash their early work. Reviving Roxy Music would only have made sense were they to have returned with something as revolutionary as the first time around.

How about the Roxy Girls then?

Tags: art, Bryan Ferry, Duchamp, fashion, Giorgione, Lil' Beethoven, Lou Reed, Manet, Metal Machine Music, nostalgia, Olympia (album), Olympia (painting), Roxy Music, Sleeping Venus, Sparks, the "Fountain" principle, Titian, Venus of Urbino

Posted in art, fashion, music | Comments Off on Olympia v the Roxy Girls

August 19th, 2010

"Paris", Moshi Moshi Records 2007, artwork Edward Gibson

It’s touching, because it sounds so naïve – just saying “One day we’re going to live in Paris” already marks you out as a starry-eyed innocent. Paradoxically, it might mark you out as unimaginative as well – as dreams go, it’s hardly exceptional in these days of incessant pressure to try and explore everything within reach of transportation, and then try and find something beyond it (because to be satisfied nowadays is to betray your own potential; worse even, you’re refusing your sacred duty to keep the economy running). Neither difficult, nor original, dreaming of Paris is conventional, provincial even: it ushers in nostalgia, it’s old-fashioned; it almost smells of under-achievement, one should really be striving to spend one’s next holiday in another planet or bungee-jump from a satellite.

Not that any of this should have even crossed the mind of the boy who sings Friendly Fires‘s Paris (who may or may not be Ed McFarlane). But it’s precisely the simplicity and the intensity of this wish that make the song so powerful. Unlike the narrator in Opportunities (Let’s make lots of money), who strives to be cleverer and more manipulative than everyone else in a world of schemers (and, by Neil Tennant’s own reckoning, is doomed to fail), the boy who promises to take his friend (lover?) to Paris doesn’t come across as even knowing the word “cynicism”. It’s an affordable dream, he doesn’t have to trample over anyone to achieve it. However…

Tags: Friendly Fires, music, Opportunities (Let's make lots of money), Paris (Friendly Fires song), Pet Shop Boys

Posted in music, rants, the way we live now | Comments Off on Paris