Tativille 1: “Le monde entier devient une clinique”

(the whole world becomes a clinic)

Jacques Tati launching into the construction of "Tativille". Ph. André Dino. All pictures © Les Films de Mon Oncle.

Assuming it is well made enough that the handle won’t slip off during use, a knife will only be dangerous when employed dangerously. Likewise, under similar assumptions, architecture and technology will be as good or bad as the uses to which they are put. Le Corbusier wanted his houses to be machines for living in and, whatever you may think of his grand urbanising designs (I, for one, am glad he couldn’t convince the French authorities to raze half of the Rive Droite to the ground), a walk through the full scale model of one of his unités d’habitation at the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine should convince you that these present no inherent danger to the soul, just the opposite. (Better yet, it is possible to visit the real thing at the Cité Radieuse in Marseille.) Le Corbusier (as Walter Gropius before him, and Otto Wagner, and others) intended to benefit the population above all else; budget was always a concern, yes, but only after human needs (as he saw them) were attended to. In less idealistic hands, this order was reversed and the idea was soon being reproduced randomly, thoughtlessly, but most of all cheaply, a bit everywhere; neglecting elements as varied and vital as the proportions of the apartments (based on the Modulor anthropometric scale of proportions he devised); the careful inclusion of well-cared, well-landscaped green areas (not just stretches of lawn), as well as commercial and service units; the enlivening use of colour and material. In the end, the machines for living in often turned into human crating by misapplication (wilful or not) of cost-effectiveness. This resulted in the sort of buildings that actually merits the Prince of Wales’s quips. [1]

Jacques Tati never finished explaining that Play time (1967) was not a manifesto against modern architecture or modernity in general. (“I’m not very intelligent but I am not going to tell you that we should build small schools with tiny windows so that the pupils won’t see the sun, and that hospitals with dirty sinks, where one was badly looked after, were brilliant.”) By then, he was schooled in such charges: they had been levelled against his previous film, Mon oncle (1958), which covered a miniature of the same ground as Play time, from a more sentimental, less ambiguous angle. Objections notwithstanding, Mon oncle was an international triumph among critics and public; won multiple awards; was hailed as his masterpiece. As it happened, Tati disagreed. He felt he had relied too much on traditional narrative, taken a step back from the nearly plot-free Les vacances de M. Hulot (1953), and in doing so, lost his way, been distracted from what he really wanted to do.

Mon oncle’s criticism of modernisation was unsophisticated. Sincerely, willingly naïve – as befits a film whose protagonists are a child and a somewhat child-like adult – it centred on a simple opposition between a traditional, relaxed lifestyle and tightly organised modern ways, neither of which bore too close a resemblance to actual life in 50s France. (Truffaut described it as “a film about the present where the present is never shown.”) It got Tati branded a poujadiste. He was already perceived as a dewy-eyed nostalgic; fairly enough, as nostalgia was one of the key colours on his palette, and he employed it masterfully. To view him as reactionary, though, was unthinking.

Tati was fascinated by gadgets, innovation and technology. His house in Saint-Germain-en-Laye was full of the real-life counterparts of Mon oncle’s Arpel House’s mod cons. If not perhaps a cutting-edge innovator in filmmaking technique, he was attentive to new technologies and keen to try them out. Nowhere in his work can we see anything as brutal as the scene in Modern Times (1936) where the Tramp is swallowed by the cogs and wheels of the machine he is supposed to be operating. In other words, Tati wasn’t against progress; rather, he was horrified by the worship of progress, which he saw as a highly destructive form of collective madness.

What was being destroyed, in his proudly populist eyes, was human relations, and with them the human soul, particularly individuality. Not that he would have discussed the matter in such grandiose terms in his films; he was definitely not an intellectual, and he was too lyrical, too refined to indulge in tub-thumping. (He started out as a mime artist in music hall, and that peculiar combination of abstraction and physicality would inform all of his work.) This applies to his cinema only; the press was a different matter, and he would speak his mind freely in interviews. Take, for instance, the South Terminal of Paris Orly Airport. Inaugurated in 1961, it was celebrated as an architectural landmark and a symbol of French modernity; for a while, the Sunday destination of mesmerised Parisians. Well, Tati made no bones about calling it sterile, odourless, inhuman, uninspiring. (“And it won’t be the tiny plate of packaged food they get served in the plane that’ll make their nostrils work.”)

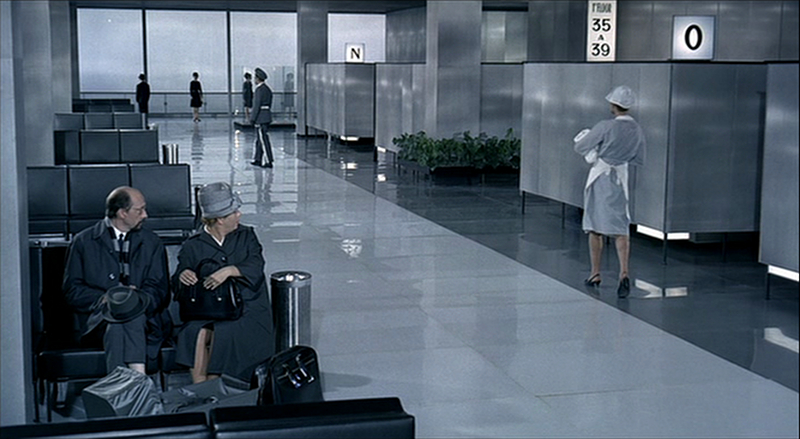

Screen capture from "Playtime" (1967, dir. Jacques Tati, ph. Jean Badal / Andréas Winding): Orly Sud.

Orly Sud would become one of the major inspirations for Play time. Tati set the film’s “first act” – or is it a prologue? – there, and even filmed some – not all – of it on location: one of the very few locations used in a production that ultimately required the building of an entire city, “Tativille”, on a vacant lot close to Gravelle, Joinville. The costs of the production, never recouped, eventually bankrupted Tati. The original idea (from Jacques Lagrange, a painter and Tati’s co-writer in Play time, M. Hulot and Mon oncle) had been to build real commercial buildings whose units they could sell off afterwards, with minor modifications, as offices and flats. Tati then decided he wanted the resulting buildings to be used as a studio complex by other filmmakers and film students, and secured a promise from then-Minister of Cultural Affairs André Malraux that this would be the case. As it turned out, Malraux did not hold true to his word once Tati ran into financial trouble, and the sets were torn down. [2]

Back to airports: already unimpressed by Orly Sud, Tati would be utterly aghast at Roissy Charles de Gaulle, a few years on (1974). The tone of his statements at the time (“you’d think the fellow who conceived that monster had dedicated himself to the suppression of all warmth and all humanity”) was worthy of Brian; although, unlike HRH, Tati never commented on aesthetics or design – all he was concerned with was what he perceived as the barrenness of the place. And indeed, you’d be excused to mistake Play time’s Orly for a hospital, at first sight.

So, no, you couldn’t call Tati a flag-waving progressive. Nevertheless, Play time’s argument about modern architecture (and progress in general) is far more nuanced than “for” or “against”. Arpel House may have been a parody of International Style architecture, but it was silly and affectionate; in Play time, architecture isn’t farcical at all. The buildings provoke awe, and the camera is clearly enraptured as it glides along them. The problem lies with their accumulation: Tati opposed what he saw as dominance and misuse. He said more than once that if he had been against modern architecture, he’d have shown ugly buildings; he did the opposite. Tativille’s metal and glass landscapes can be bleak, desolate even, but you cannot fail to register their austere beauty, which is not accidental. (Not the minutest detail is: one of the many wonders and contradictions of Play time is that a film so rigidly planned should be one of the great works in praise of spontaneity.)

It wasn’t the buildings, then (although some are clearly better than others). Tati worried about the indiscriminate proliferation of modules everywhere, without concern for suitability, adaptability or the diminishing returns of repetition. (As Dalí once said, “the first man to compare the cheeks of a young woman to a rose was obviously a poet; the first to repeat it was possibly an idiot.”) About the mechanisation not only of work but of thought and behaviour; the abandonment of individual creativity – of personality – for mass production, standardisation, streamlined practicality. The kind of progress Tati opposed was rigid, unaccommodating, it elbowed out any way of life that did not fit its patterns: no doubt, cities made up of endless rows of identical buildings would require undifferentiated people to inhabit them.

Had Play time not been released the previous December, Tati might well have used the May 68 slogan “l’imagination au pouvoir!” for its publicity; more than a perfect tagline, it works as a plot summary. It would have been somewhat misleading to have used it, however, for, while critical of the way things were turning, Tati had no revolutionary intent and certainly did not want to overthrow anything at all. He wasn’t a young man any longer, nor was he marching precisely in step with the zeitgeist. (That would have been Godard.) This did not deter Tati from later claiming that with Play time, he too had been “in the barricades”. (It wasn’t taken as gospel.)

Mysteriously enough, he could have claimed he had filmed a philosophical tract he couldn’t possibly have read (it was published one month before the film came out, and at any rate Film Tati nº 4 – as it was known at first – had been in gestation since at least 1959). This was Guy Debord’s La société du spectacle, one of the key texts of Situationism, a movement Tati may well have ignored, and might not have cared for had he been aware of it. (He was never particularly inclined towards philosophy or politics.)

Debord described a society in which every relationship is mediated and commoditised, where no rapport is more than its own representation: “The spectacle is the moment when the commodity achieves full occupation of social life. Not only is the relation to commodity visible, nothing else can be seen: the world one sees is its world.” This process of domination of all social life by economy would have happened in two stages, the first of which would have “dragged into the definition of all human achievement an obvious degradation of being into having”, whereas the current phase led “to a generalised slide of having into appearing, where any effective ‘having’ must find its immediate prestige and ultimate function. At the same time, all individual reality has become social, directly dependent on social forces, fashioned by them.”

The Situationists were of Marxist orientation and wanted to overthrow such a state of things. They supported the May 68 student revolt, in which Tati (not a Marxist by any standards) would never have participated. But they also advocated far more playful and creative means of resistance, amongst which that of the dérive – a “technique of impulsively passing through various environments” whilst letting oneself “go along with the temptations of the terrain and its corresponding encounters” and affirming “a fun constructive behaviour”: practically a description of how Hulot negotiates the city.

This is how we can have a conservative sensibility aligning with a revolutionary agenda. While the Situationists opposed what they understood as the consequences of a complex historical and political process, Tati, more simply, saw a threat in the unthinking rejection of the “good old ways” in favour of streamlining and mass behaviour. In other words: bring on the future, but not at the cost of erasing the past. The most incisive illustration of this comes in the Ideal Home section, when Tati shows us precisely what place he fears classical culture is likely to occupy in modern homes.

This is perhaps the one blatantly aggressive image in the whole film; as a rule, even the sharpest criticism is delivered in the breeziest of tones. Play time is as gentle as it is funny, and it can be very funny. Not always, however: many of its gags are as likely (if not more) to provoke melancholia. For example, when Barbara (Barbara Dennek, a non-professional – like most of the cast – in her only cinema role) is about to walk into the Ideal Home exhibition and catches a reflection of the Eiffel Tower on the glass door; she pauses, and looks back wistfully.

There is but a handful of sights of a recognisable Paris in the entire film, all of which will appear only as reflections on glass doors. (The gag works by accumulation: the sadness of the idea dissipates a little each time, until the final iteration is purely amusing, and to an extent even slightly defiant.) Decades later, Polanski would riff on this in the excellent opening sequence of Frantic, a taxi journey from an airport through a barely identifiable city that only “becomes” Paris with a brief sighting of the Eiffel Tower in the background, as the taxi reaches the hotel. [3]

Play time keeps coming back to this idea. One of the sight-seeing destinations for the group of tourists we are accompanying is a tour agency covered in near-identical posters representing travel destinations all over the world.

Art Buchwald expressed surprise at the prominence of the credit he received for the film’s English dialogues, which he regarded as nothing much. He was either being disingenuous or underestimating his own work. While you certainly don’t need any dialogue to make sense of Play time, the sting in some of Buchwald’s lines adds considerably to the satire. Perplexed by the London poster in the tour agency (featuring the same building as in all the others, with the Clock Tower behind it and a red phone box in front), Barbara is urged by one of her friends to come and see the sights. She complies, dutifully.

Play time’s gentleness may well have been one of the reasons it performed poorly at the box office. If one wanted zaniness, Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le métro (1960) had set the bar surrealistically high; if criticism, the times demanded the take-no-prisoners approach of Godard’s contemporary Week-end, which, with its corrosive satire, its cannibalism and its spectacularly bloody traffic pile-up (which may or may not have resurfaced, of course cleansed of blood and guts, four years down the line in Tati’s Trafic), hit a nerve Play time couldn’t (and did much, much better at the box-office). Regardless, Play time can be withering. Barbara is supposed to distinguish herself from the other tourists through her sensitivity, her ability to connect with and appreciate what remains human and individual in the great homogenisation. Yet it is she, in still another scene that seems rather less sweet in retrospect, who thoroughly de-humanises (and exploits) a little old lady selling flowers at a busy intersection.

Barbara does not mean any harm, but she is incapable to respond to the flower seller as a person: all she sees is an image – “this is the real Paris!” – to capture; and her attempts keep the lady from doing any business, as any potential customers are shooed away so as not to disturb the ideal photograph. Photo taken, Barbara merrily goes away, without a thought of buying any flowers or compensating the lady for her inconvenience or loss of earnings. You don’t need Marxist analysis to spell out the finer points of this.

(Having said that, this reading is complicated and made ambivalent in the closing section of the film, where M. Hulot helps Barbara to finally get her photo. It is all arranged pretty swiftly with a second flower lady, without apparent inconvenience or disruption to her business, and a passer-by who is “perfect” is roped in to pose as well. It is worth noting that this happens in the morning after the destruction of the Royal Garden, after the world has changed.)

There is some slapstick to be had with the idea of exploitation too. At the Royal Garden, a waiter tears his trousers on one of the spikes from the crowns that decorate the backs of the restaurant’s chairs. (These are the same crowns that get imprinted on patrons’ backs.) The unfortunate waiter gets immediately shunted out of view – out of the restaurant itself, in fact – and from employee, turns into a spare part repository: his colleagues start to scavenge him for articles of clothing, item by item, whenever they soil or damage any of theirs.

Despite such moments, Tati isn’t particularly insistent about social inequality, nor does he attempt anything approaching economic analysis. How money is made doesn’t concern him, and there is no real sense of the importance of money to keeping Tativille going. (This is curious, when we know he must have been fully aware of his own impending financial ruin even as he made the film.) Tati was never a political filmmaker, but he was a populist filmmaker, and in Play time, as he had already done on an intimate scale in Mon oncle, he is questioning whether the new is really all that better than the old it is replacing. What social commentary there is is naïve, and Tati never claimed otherwise. But in Play time, by keeping the sentimentality of Mon oncle (not necessarily a problem in the context of that film) mostly at bay and working at city rather than individual level, he highlighted some very real problems.

Play time feels somehow more relevant to our present day than to 1967; it hits spots Tati couldn’t possibly have predicted. Tativille’s blocks of flats are beautiful, radiant, spacious, harmoniously proportioned. They display the exact same chairs used in office waiting rooms, and their windows, full-length glass fronted, opening out onto the pavement, are shop windows.

Residential and commercial blocks are therefore identical; never mind work/life balance, this leads to the merging of work and life (those chairs again). This point is far stronger 45 years down the line, with work/life balance long gone out of the window (you are never out of reach with a smartphone) and we are encouraged to apply a marketing mentality to every last interaction in our lives. (How different, for instance, are a dating and a job search website?) And friendship has of course been made into a quantifiable commodity via all the social networking products that urge us to “share” (broadcast, rather) all our thoughts, deeds and life. If this is in itself a bad thing is down to each person, but there is no doubting it is very good for business.

And so it is that Mme Arpel’s refrain “tout communique” from Mon oncle carries over visually into Play time to provide a perfect metaphor for life on the Internet.

I am of course not suggesting Tati was thinking of web-based intimacy in 1967. Still, the metaphor fits, and there can be no doubt that he was commenting on the disappearance of privacy. The difference is that in Tati’s scenario, this was a casualty of the new lifestyle: people were merely going along, probably without thinking (there is no way of telling; Play time is one of the least psychological films I’ve ever seen). Whereas nowadays everybody is aware of what is happening. (Hang on…)

Not that anybody in Play time seems unhappy about this state of affairs – not even M. Hulot, outsider par excellence, seems to feel anything worse than slight embarrassment at his own maladjustment to the surroundings. No, Tativille’s citizens are perfectly happy, its tourists delighted; everyone is integrated. Play time’s Paris could be a version of Huxley’s brave new world where the rulers need no soma to keep the population happy because the lure of the lifestyle is enough to dispense with any need for transcendence, spirituality or self-awareness. Tati does not quite pass judgement on such a state of affairs; there is no character in Play time to match Brave New World’s John. If M. Hulot is wary of or upset by anything he sees or does, he keeps his own counsel and does his best to fit in. Tati is measured and subtle enough to suggest that, regardless of what he himself might think, Tativille could indeed be the best of all possible worlds, to those who suit it. (This would never have been the case with the Situationists.) We must make our own minds up as to where we belong.

He of course leaves no doubt as to where he (not Hulot) stands, and Play time turns (literally, in the end) around malfunction: at first used for comic value, malfunction eventually becomes Tativille’s redemption, the door through which the humanity Tati is so fearful of losing may sneak back in. Little mishaps keep happening, some by accident, a few only due to M. Hulot’s time-honoured balletic clumsiness, but mostly because of inefficiency. Things are too complicated to operate, too elaborate or too simple, plainly inadequate for their function, misleading, or a combination of the above. Having a pharmacy and a snack bar side by side, for instance, turns out to be a case where tout communique a bit trop perhaps.

From the moment when we arrive to the Royal Garden, inefficiency takes over for good. The restaurant is opening before it is finished, and absolutely everything that can go wrong, does. Dance floor tiles come off, chairs leave marks on patrons’ backs, lights and air conditioning (whose control panel is remarkably similar to the intercom featured earlier when Hulot went for his business appointment) malfunction, the kitchen window is too narrow for the trays, the glass front door breaks, food runs out and unfed patrons become progressively drunker, in an astonishingly elaborate, relentless descent into chaos that lasts close to an hour and was Blake Edwards’s confessed inspiration for The Party (1968), which could almost be considered a full-length remake of the Royal Garden sequence. Finally, Hulot, without causing it (it’s a clear consequence of shoddy workmanship), triggers the collapse of a whole side of the restaurant’s décor, and, with it, a general thawing out: in the wonky, makeshift space thus created, people can revert to the relaxed, convivial modes of socialisation against whose disappearance Tati is warning us.

This is not just the passing effect of the alcohol and the circumstances, but also the turning point of the film: the makeshift and the bonhomie carry on into the following morning, contaminating the whole of city life. As we come out of the Royal Garden, one of our first sights is a dug up portion of the pavement.

A visit to the drugstore reveals hanging electric cables and sputtering neon sights – and a convivial, intimate atmosphere where chic patrons from the Royal Garden and salt-of-the-earth workers happily mingle. (Previously, any representatives of the working class would have been clearly confined to their duties, if at all visible.) To underscore the transformation, Tati gives us the final reflected image of Paris, on the drugstore doors. It is now free from any sadness, purely a charming gag – and it happens to be the Sacré-Cœur: which is to say Montmartre, which means a benevolent presence, a blessing. And perhaps something less enchanted too: thinking of the second flower lady, Tati could be pondering whether that celebrated joie de vivre might not itself have become something of a tourist attraction.

In any case, a transformation has indeed occurred, and it is unambiguously positive. People are looser and happier, and colour has invaded the grey streets.

In fact, you could almost say Tativille has gone full circle back to the small town fair in Jour de fête (1949). There is even a roundabout!

This is what Tati leaves us with, a traffic jam that generates joy instead of numbness (as would be the case in Trafic, a few years later), a problem that solves itself by turning into a party, continuing the revolution begun at the Royal Garden and bringing about the triumph of what Tati called the indomitable French spirit. (And, in passing, providing us with a few fine examples of Situationist events.) Perhaps we could call it a triumph of the imagination; there is, in any case, a strong suggestion that progress and technology can be perfectly all right if only we make sure to have them fail us or subvert their uses from time to time, just so we never forget who should be boss. Everyone’s eyes have been opened, and if the final view of Paris that Barbara takes with her is of the same roadside lights she had seen on arrival, she now can see they are really snowdrops.

Notes

[1] HRH, rather conservative in his architectural tastes, seldom hesitates to muscle in against designs he dislikes. The most notorious instance was his speech to the Royal Institute of British Architects in May 1984, when he described a proposed extension to the National Gallery (by Ahrends, Burton & Koralek) as “a monstrous carbuncle in the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”. The extension (which wouldn’t have been a monstrosity at all) was never built, and Venturi Scott Brown provided a meekly post-modern design that was found palatable. More recently, he was in the news due to his influence over the Qatari royal family’s decision to reject Rodgers Stirk Harbour Partnership’s design for the redevelopment of the Chelsea barracks.

[2] Incidentally, Malraux’s actions as minister would turn him into an enemy to the eyes of the Nouvelle Vague filmmakers; he was responsible for the removal of Henri Langlois as director of the Cinemathèque in 1968, triggering a wave of protests, including violent confrontations with the police, which fuelled the mood of revolt already in the air at the time: some consider the Langlois protests as one of the triggers of the student revolt. It was part of the reasons for the cancellation of that year’s Cannes festival.

[3] Robert Altman used the same gag to a different effect at the end of Beyond Therapy, whose characters, supposedly in New York, spend the film talking about going to Paris. A lovely shot pulls back from the room where they are talking and talking and into a bird’s eye view of… Paris.

Quotes & Links

Guy Debord quotes (and paraphrases) taken from La société du spectacle, ed. Buchet/Castel 1967. I used the online version of the 1971 Champ Libre edition, italics as in the original.

Jacques Tati and François Truffaut quotes taken from Play time by François Ede and Stéphane Goudet, ed. Cahiers du Cinéma 2002, Jacques Tati by David Bellos, ed. The Harvill Press 1999, Jacques Tati by Jean-Philippe Guerand, ed. Gallimard Folio Biographies 2007, Jacques Tati by Michel Chion, ed. Cahiers du Cinéma 2009, and François Truffaut Correspondance, ed. Hatier / 5 Continents 1988.

Translations mostly mine. I am indebted to all of the above.

Links to names in captions: André Dino, Jean Badal, Andréas Winding, Les Films de Mon Oncle.

Tags: Aldous Huxley, architecture, Beyond Therapy (film), Brave New World, cinema, dérive, Frantic (film), Guy Debord, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jour de Fête, La société du spectacle, Le Corbusier, Les vacances de M. Hulot, literature, May 1968 Paris protests, Mon Oncle, Play Time, rants, Robert Altman, Roman Polanski, Situationism, the way we live now, Trafic